Summer isn’t only for lazing on the beach. For some College undergraduates, it’s also the time for diving into crucial research. Here are five who are participating in the Harvard Summer Undergraduate Research Village Program or received the Ethnicity, Migration, Rights Summer Thesis Research Grant.

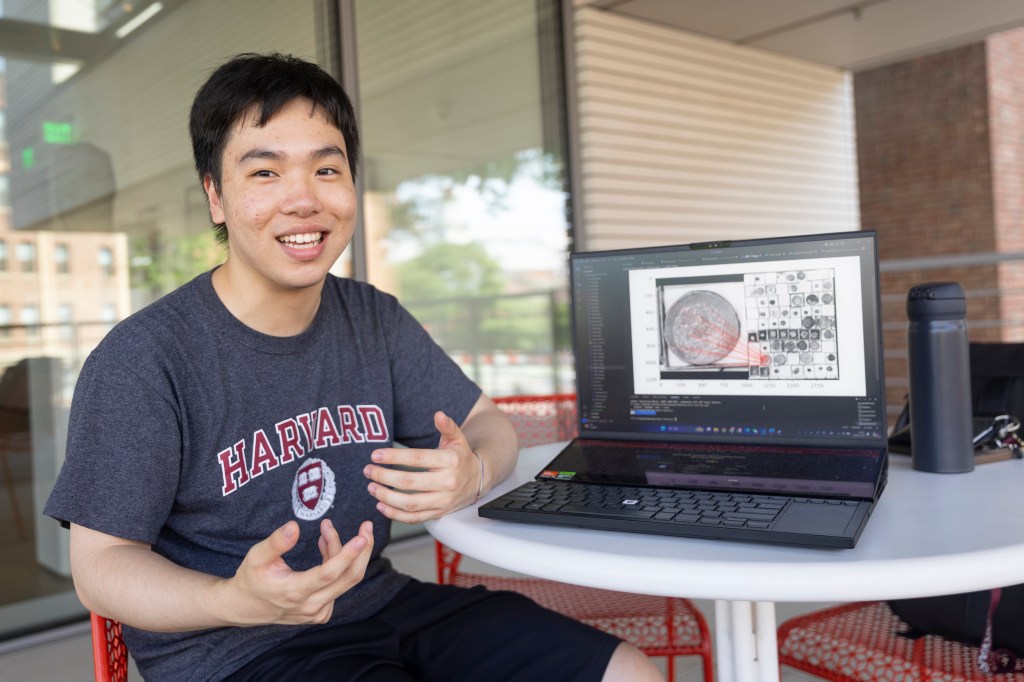

Puyuan “Alvin” Ye ’27

Ye, a prospective computer science concentrator, is working with the Coins Recovery Project to create a crawler bot that searches online auction databases with the goal of tracking down hundreds of coins stolen from Harvard Art Museums in 1973.

“You’re basically cosplaying the FBI,” Ye joked.

The collection, which included ancient Greek and Roman coins, was on loan to the Fogg Art Museum at the time of the theft. Nearly 6,000 were stolen by a group of armed gunmen who overpowered a lone night watchman, according to news reports. Most have since been recovered by FBI agents, museum staff, Harvard students, and consultants.

The Coins Recovery Project kicked off last fall with archival work on the hundreds that remain missing. The initiative continued into the spring with the creation of a database on the stolen treasures. Now, Ye is using his tech skills to pitch in.

The Summer Humanities and Arts Research Program fellow is working under Laure Marest, Damarete Associate Curator of Ancient Coins, and Jeff Steward, director of digital infrastructure and emerging technology, to comb through descriptions of auction entries. When a possible coin is flagged, Ye runs the image-matching bot, and potential matches are recorded and passed to the curator.

“This is the first time I’ve ever used my computer science skills for a real-life application,” Ye shared. “I’m learning while I’m working on this project, and I’m also preparing myself better for what I might do in the future.”

Emily Peck ’25

Peck has spent time tutoring English language learners in Boston Public Schools during her time at Harvard. The experience illuminated many of the challenges immigrant children face in the U.S. education system.

“A lot of these students were being asked to do work at an English level that was much higher than the level they spoke,” said the social studies concentrator. “It seemed like there was this huge gap that wasn’t being bridged by their education.”

Peck was inspired to research the history of bilingual education in Boston, learning about two laws that had a significant impact across the state. It turns out the city had several thriving bilingual programs in the early 2000s. But a 2002 referendum replaced multiyear transitional English education with a single year of intensive language training, effectively ending bilingual programs in Massachusetts. Fifteen years later, a coalition of advocacy groups worked to reverse the ban with passage of the 2017 LOOK Act.

This summer, Peck — a recipient of the EMR Summer Thesis Research Grant — is investigating how support for bills such as the LOOK Act emerges in the first place. The quest brought her to the State House, where she spoke to staffers about representatives’ support of the bill and how their constituencies affect decisions to endorse particular causes.

Her research is helping her learn more about the democratic process, but it’s also informing her views on best practices for improving bilingual education for immigrant students.

“Public schools should assess the needs and wants of their students and parents and the achievements of their students,” she said. “From there they should decide what program would be best.”

Abel Rodríguez ’27

What began as a first-year seminar turned into a summer research opportunity for Rodríguez. The rising sophomore is participating in the Foundational Undergraduate Experience in a Laboratory (FUEL) program, which exposes students to the world of lab research.

One of 10 students participating in FUEL, Rodríguez is studying porphyrins — a group of macrocyclic compounds that are aromatic and absorb light — and how to synthesize them for cancer treatment.

Along the way, Rodríguez, who hopes to concentrate in chemistry, is also picking up lab techniques, safety, and social norms for those working in a lab.

“Coming to a place like Harvard, I had this notion that everything that people will do will be immaculate,” Rodríguez said. “But being in the lab surrounded by so many bright people and seeing their mistakes … It’s changed my perspective in the sense that when I make a mistake in the lab, this is where I’m really learning and growing.”

The experience also clarified plans for his academic career. “The program was the last step I took toward figuring out what I really want to do,” he said. “It has established for me that I want to go into the sciences. I want to engage in research.”

Shruti Gautam ’25

Interning with public defenders in New Orleans last summer led Gautam to discover a local gem known as Lincoln Beach, a former Jim Crow-era amusement park and recreation area for Black residents that was closed after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act but is still used by locals.

A year later, Gautam, a history concentrator with a secondary in neuroscience, is back in The Big Easy, this time as an EMR summer thesis-research grant recipient. Now she spends her days combing through city archives and land documents or analyzing old maps to learn about the beach’s history.

She also is working with community members organizing to make Lincoln Beach safer, cleaner, and more accessible.

“Histories of small properties are the best way to explain a much larger, complicated history,” the Mather House resident said. “For New Orleans, it’s incredibly important because the histories that are written about the city are often mythologized and make this city live in its past. Everything is focused on its French colonial history, or jazz … and not an actual true history of the people who are still there.”

Before settling on Lincoln Beach as her thesis topic, Gautam learned more about its history last fall during a Harvard Law School class on labor history and the law. While researching a course assignment, Gautam learned that the privately leased and run beach under public jurisdiction had been managed for part of the 20th century by local Black community members, many of whom were also unionized.

The beach sits on Coushatta tribal land and was previously owned by United Fruit Company President Samuel Zemurray and the public-private Orleans Levee Board.

On July 10, the beach was designated as part of the National Registry of Historic Sites, an important development in its preservation and planned redevelopment.

Gautam was particularly interested in the site’s identity as it transitioned from tribal land to an important gathering space for Black and Latinx communities. “I came to the conclusion that it never really transforms how people associate themselves with the land,” she said. “What it does transform is who companies decide they want to be able to access the land.”

Kayla Reifel ’26

The History of Science concentrator is spending the season processing a new series of Polaroids of historical scientific instruments and creating a mini exhibition for display in the foyer of her department at the Science Center.

The department is home to the collection. “It’s a pretty small museum and small staff, so we get to really be deeply involved with all different facets,” Reifel said.

The opportunity is part of the Summer Humanities and Arts Research Program (SHARP) and includes research on the instruments themselves.

“One of the most interesting things I’m learning about is the ethics of museum collecting and displaying,” Reifel said. “It’s been really interesting to hear about what’s acceptable and what’s not when it comes to accepting donations and displaying things in a certain way.”

Reifel has even learned how to handle the historical instruments. “My work this summer has made me think a lot harder about education and what considerations we need to have to think about when it comes to teaching science and the history of science,” she noted. “It’s also allowed me to develop this ability to really find joy in whatever I’m researching.”

Reifel feels she is now better equipped to advocate for the importance of historical research. “This experience really made me realize how important it is to tell the stories of the history of pretty much anything,” she said. “If you don’t know the history behind something, then you don’t know what you’re doing.”

Source link